So I wrote a JSON API Framework and the Framework was the Least Interesting Part

First a little background

I’ve always been a big fan of REST the way Roy intended it for two major reasons:

It uses HTTP the way HTTP was intended, playing on its strengths and not wasting any time re-inventing what HTTP already has. The state of HTTP APIs these days is really ridiculously bad, given what we should have learned from the unfathomable success of the WWW. I was also envious as hell at the great framework Erlang developers had in Web Machine . If you write HTTP APIs for a living and you haven’t seen HTTP mapped to a state machine, you really owe it to yourself to check it out. It’s brilliant.

The thing I really wanted to do though was make web APIs not so terrible. There are a few reasons that I think they’re terrible:

- You have to read reams of documentation to do the simplest things, like finding the URL for something.

- You have to hard-code urls all over your client app.

- When you do something wrong, there’s no consistency in error output.

- Knowing HTTP doesn’t make it any easier to predict how something will work.

If you rely on someone else’s API in your day-to-day work, you probably know what I mean. I’m not going to name any names (but here’s a clue: one of the worst offenders starts with an F and rhymes with Facebook).

So the APIs I wanted to make and to use would be:

- semantically consistent with plain old HTTP

- discoverable, like other pages and controls on normal HTML web sites are discoverable.

Luckily HTTP is also the vanguard of API discoverability, most often in the form of hypertext (So that’s what that H stands for!) . I’m a bit blown away that this wasn’t obvious to me earlier, but luckily I stumbled into Roy Fielding talking about hypermedia and I realized that that’s precisely the correct way to solve the discoverability problem. He was saying real REST APIs should minimize out-of-band knowledge by leaning on what HTTP’s already got: links! [^1] .

Then I saw Jon Moore make it real with an XHTML API . XHTML forms are a method of discoverability as well?!? My mind was blown. Think about that: XHTML documents tell you what kind of write-possibilities the API has. You don’t need to read docs to find out!

And then I saw Mike Amundsen bring it all back to json and I knew it might be something I could actually use in the real world and people trying to Get Stuff Done wouldn’t want to hunt me down and murder me in my bed (especially since I’m also a card-carrying member of the People Who Want To Get Stuff Done Liberation Front). I think most of us are of the belief that XHTML isn’t going to unseat json as the preferred media-type for APIs anytime soon.

Armed with all this inspiration, I wrote a web-framework. I ended up picking node.js mostly because the HTTP line-protocol stuff was already covered there without any extra cruft to get in my way, so I was free to try to aim for “Web Machine with json with links”[^2], which I call Percolator. The framework isn’t the interesting part though; it’s the stuff I learned along the way, which can be done in any framework/language/platform, even if it’s not baked into the framework.

The First Interesting Part: Hypermedia apis are indeed awesome

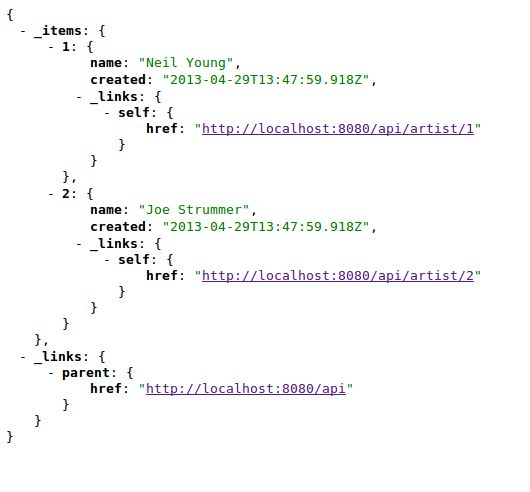

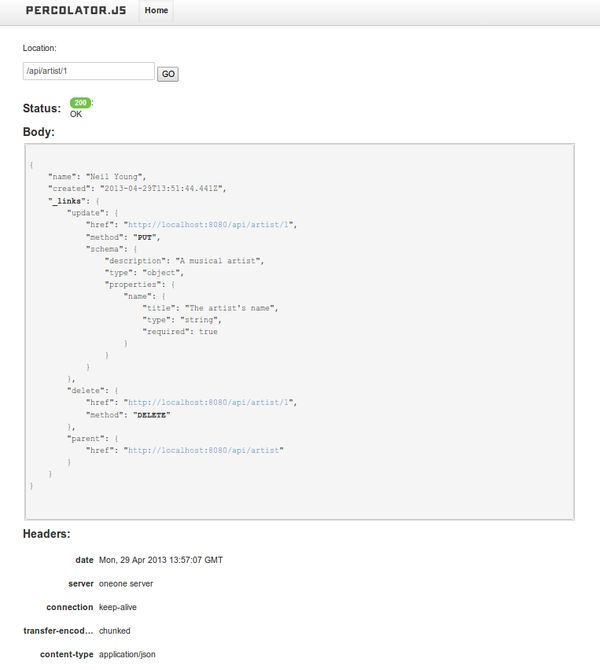

I started by just putting links in my json to other endpoints that make sense. That made my json APIs so much easier to use, even when the user is me. I had one endpoint for my entire API and every other endpoint was discoverable by following links. I used JSONView for Chrome and for Firefox and I could click around my entire API testing the GET method on every endpoint just by clicking. Here’s how it looks:

Those purple links are visited links that you can actually click on and get a new API response. I showed some co-workers that were using my API and eventually they stopped asking “Hey what’s the URL for getting X again???” They could always easily re-find it themselves.

Adding links also pays off when humans aren’t involved. In many cases it means that the client doesn’t need to construct its own links. For example: when one of my APIs was being used for replication by a client app the client developer asked how we’d handle pagination, because he wanted to page through all my results to replicate my API’s data elsewhere (sort of like how couchdb replication works, which is simple yet amazing ) . I had a pagination scheme working, but it didn’t make use of the database indices as well as I wanted so I told him instead to just follow the ‘next’ link and not to worry about the parameters for constructing the URL at all and that the absence of a ‘next’ link would indicate the end of the results. What this meant for me is that when I changed the pagination scheme to something more friendly to my database, I didn’t even have to tell him. What it meant for him is that he never had to change anything on his side to support the new form of pagination, and he didn’t have to construct any urls.

It blows my mind that pushing this simple technology further could end up with clients ONLY needing to store the root URL of the API, and not a who’s-who of possible disparate endpoints that practically mirrors the routing table on the server. People are actually starting to push the envelope this way. Wouldn’t it be great if at some point we could stop writing client software that’s hopelessly service-dependent ? Wouldn’t it be great if one day client-side url construction was considered as silly as using regexes to get data from json?

I should also add that even if you’re writing both the client and the server, which happens a lot with single-page apps and mobile apps, you might be tempted to think this is a waste of time, but in my experience it makes testing and debugging much easier and helps me remember what my API does after a month without using it despite my terrible memory. That minor extra effort of adding links pays for itself over and over again.

Interesting Part #2: JsonSchema is surprisingly awesome

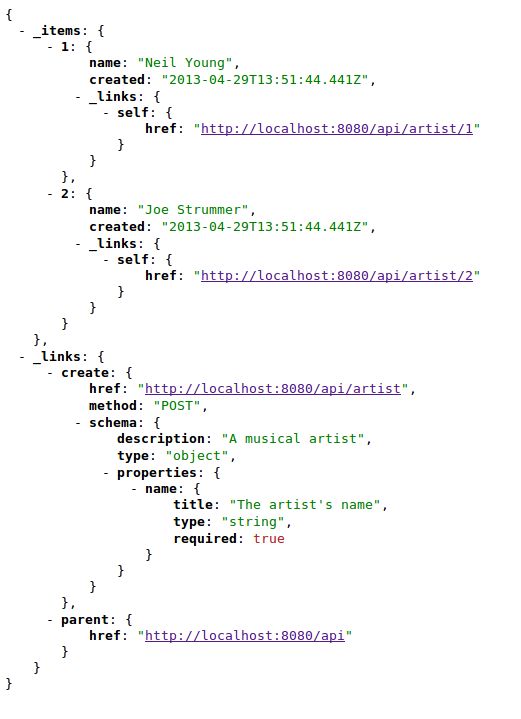

Of course once I could surf around my API, it didn’t take long for me to bemoan the fact that I could only peruse GETs this way. I had seen Jon Moore’s XHTML API demo (This is my third link to it here, so you know it’s worth a watch!) , and I was jealous of how XHTML forms could describe the POSTs as well. Originally I decided that json needed forms as well, but the big brains in the Hypermedia-Web Google Group convinced me that I could just expand my link concept to know about other HTTP methods. And I had already stumbled upon JsonSchema as a way to specify what was expected in a PUT or POST payload, just like XHTML forms can do (but still using json of course).

JsonSchema is a particularly elegant solution to the problem, because I can write all my validations in JsonSchema, publish the validations as json to the api (JsonSchema is just json afterall), and then on the client side re-use them for validations before I even bother with an http request to the api. This way I can use the same validations on the client and server, AND communicate them naturally as part of the json payload. The end result was that my json APIs could now fully communicate everything that was possible via the json API itself. Here’s how it looks:

I added baked-in JsonSchema support to Percolator right away of course, but you can do it easily in any of the most popular languages ( see the validators tab). Currently I haven’t implemented any clients that use it for validations yet, but I do use it for my server-side validations. More importantly still, it communicates to humans everything that’s necessary for a successful PUT or POST. [^3]

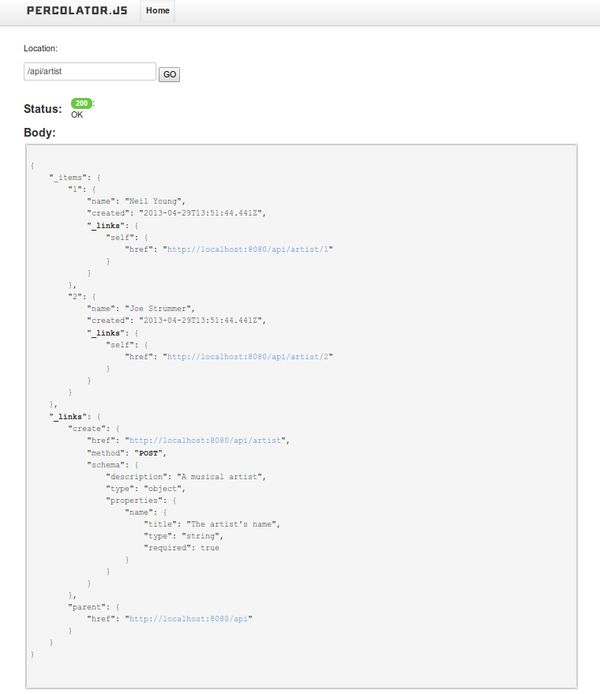

Ultimately the addition of JsonSchema lead me to add a static frontend to Percolator that, after abstracting it away, I published separately as the Hyper+JSON Browser . You don’t need it, but you can use it in conjunction with Percolator apps to ‘browse’ them even more easily than JSONView does (and without installing a plugin). Any app (using any language/framework) that spits out the same sort of output as Percolator could use this the Hyper+Json Browser just the same, because it’s a static single-page app that works over any API that works similarly. Here’s how it looks in use:

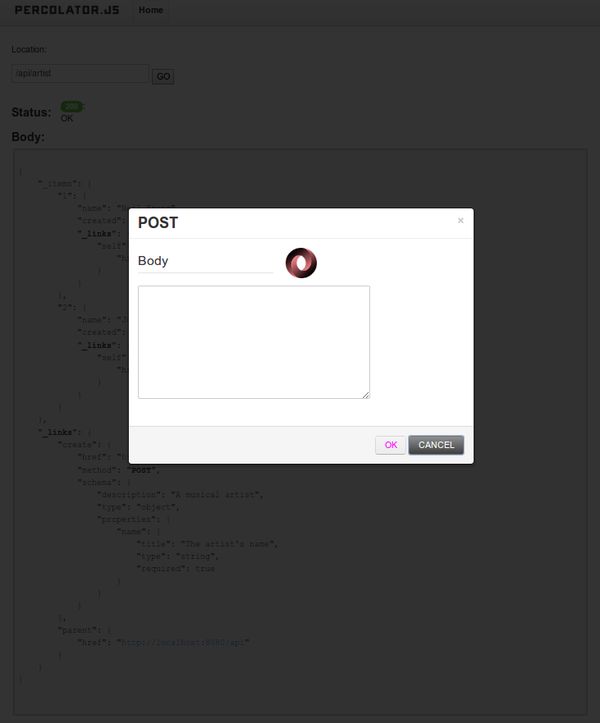

When you click on that ‘create’ link to POST, it does this:

Browser after clicking the POST link

That red json logo indicates that you haven’t entered valid json (yet). Pressing OK will actually POST the json that you enter and show you the result.

Here’s a view of another resource (an individual item in the list from the previous collection resource, which can be found by clicking that item’s 'self' link. It shows delete and update links for this particular resource.

People have likened this to the Django admin interface, which is a huge compliment, not only because the Django admin interface is pretty legendary, but also because this frontend doesn’t know a single thing about the API other than the requirement that the API uses the aforementioned link format. This is an area where I’m really excited: In what other ways can other programs use these APIs without foreknowledge? (I’m not really talking about intelligent agents – they’d need to understand a little more than the API provides — but dumber things that still use human interaction eventually, like automatic HTML form generation, are mostly possible.)

(Somewhat less) Interesting Part #3: Object-oriented routing leads to less stupid stuff

I hate to sound old-school, but sometimes the object-oriented paradigm maps to a problem better than a functional one. In this case, I’m talking about routing. I don’t know why the HTTP methods GET, POST, PUT, etc are named “methods” but it sure does make perfect sense, because each one is tied to a particular “resource”: that “thing” you’re interacting with by using the HTTP methods for a given URL. It should be obvious then that HTTP resources should be the thing we route to, and not disparate methods. REST APIs are supposed to be the antithesis of RPC, but when routing involves the method as well, developers tend to make less RESTful APIs and framework developers tend to mess up some of the finer points of HTTP. Here’s a quick test:

- Grab your favorite web framework and create a resource with a single GET handler.

- POST to it. Did you get the proper 405 response?

- send an OPTIONS request. Did it tell you that only GET was available?

Probably not. Web-machine gets this right because it routes to the resource, instead of disparate functions that when imagined together form a resource. I wrote Percolator to work like web machine in this way, because I wanted my APIs to look like something other than a haphazard collection of RPC calls without requiring a lot of self-discipline. The result is that Percolator responds with 405s when a client tries a method that that resource doesn’t support, and also responds to OPTIONS requests with a list of all the allowed methods. The result again is better discoverability without reams of documentation, and better feedback for client developers when they’ve done something the API doesn’t support.

There are advantages to OO routes for application developers to though, organization-wise:

- All routes for a particular resource are connected to that resource, so there’s no chance of sloppy intermingling in the source code.

- A bunch of code that you have to write in each method can be written just once for the resource.

- You start to see patterns in what resources do, which can lead to certain classes of resources that can be re-used over and over, sometimes wholesale and sometimes with particular strategies that change them slightly. This is a bit of a big deal, in my opinion because it’s extremely rare that I see this kind of re-use in web applications in the real world.

Anyway: Percolator is indeed ready for production use (at least for the use-cases for which I’ve used it in production!). It’s extremely fast and extensible, and I hate it a lot less than anything else I’ve used for json REST APIs.

Hopefully it helps someone make a nice API, or it gives some other framework developer some new ideas. The APIs we have today cannot possibly be the best that we can do.

[^1]: plus a pile of other conventions

[^2]: Ultimately I diverged quite a bit from Web Machine, but it was always a huge inspiration.

[^3]: Alright not everything, but a heck of a lot. Linked documentation on my RELs would be another huge boost to discoverability.

Tags: api, rest, programming, open source

← Back home